William

Langley of Lichfield

“Trust but Beware Whom”

A Genealogy of the Langley family

Author: Peter Langley

July 2002

with contributions from

Maj. Gen. Sir Desmond Langley KCVO, MBE.

Susan Bradbrooke, Archivist with the Agecroft

Museum, Richmond, Virginia.

Click

here for the Ancestry

of the Lords of the Manor of Prestwich. Starting with Robert de Prestwich born 1150, through to Thomas William Coke, the last Lord of the Manor of Prestwich.

Table of Contents

1. The Origin of the Name Langley.

5.1. RICHARD DE LANGLEGH – c.1325 to c.

1369.

5.2. ROGER DE LANGLEY – 1360 to 1393.

5.3. ROBERT DE LANGLEY – 1378 to 1447.

5.4. SIR THOMAS of Agecroft 1407-1472

5.5. JOHN of Agecroft died 1496

5.6. ROBERT of Agecroft, 1462 to 1528

1. The Origin of the Name Langley.

During

the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, one of the newest inventions was a last

name or surname. Before that you were simply Robert, William or John. Surnames

usually came from one of four different sources. If your occupation was to sell

meat then you became John Butcher. If you were the son of Stephen you became

John Stephenson or John Fitzstephen. If you had White hair, then you became

John White. If you were from an area called Langley then you would become

William of Langley or William de Langley. This was a territorial name, and

slight confusion arises from people moving from one area to another and

consequently changing names.

Therefore, as

Langley[1] is

a territorial name, our ancestor must have lived at a place called Langley.

2. Where was this Langley?

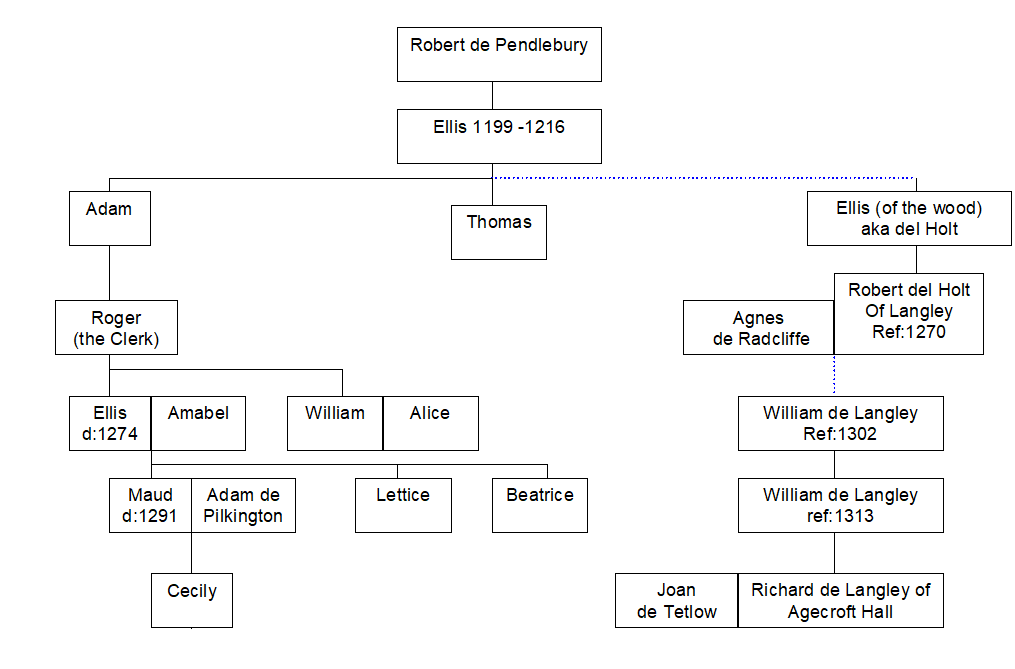

The tree drawn

up by Alfred Langley in the late eighteen hundreds shows the Lancastrian

Langleys descended from Geoffrey de Langley of the third crusade with no

indication of where he got the name. The tree proceeds to indicate that our

branch settled in an area of the Manor of Middleton in Lancashire in about 1350

and gave our name to it.

However

research has shown that this area called Langley was in existence prior to

this, and so it is more than likely that this is where our name originated and

we do not descend from Geoffrey.

The Victorian

History of Lancashire tells us that in 1270, Sir Geoffrey de Chetham sold

tenements in land called Langley to Roger de Middleton. Robert, son of Elis del

Holt and heirs holding this property by homage and service.

In 1302 comes

the first mention of a Langley, when William de Langley attested a Hopwood

Charter. Who was this William de Langley? At the moment we can only guess. The

Langleys of Shropshire incorporated the Pheon as their crest; this was the

crest of the Holt family so we can assume he was descended from Robert del Holt

as mentioned in the previous paragraph. The Cockatrice was also used

extensively in the Langley family, this is supposed to be the Pendlebury crest.

Using my imagination, here is a possible early tree…

Eleven years

later, in 1313, William’s son, another William, was called upon by Sir Roger de

Middleton to defend his title to certain lands.

This second

William had three sons that we know about.

1. William, born about 1316, became Rector

of Middleton in 1351 and died in 1376. He appears to have been the patriarch of

the family

2. Unknown son, he is unrecorded and little

is known of him. He could have married a Hopwood heiress which would account

for the Paly shield being used by his descendants. It is believed that the

Hopwood family owed their origins to a younger son of a Middleton. This unknown

son had a son William who married Alice, daughter of Thomas de Barton of

Middleton and his wife Maud daughter of Roger de Middleton. William and Alice

had amongst others, three sons. William of Langley, from whom descend the

Langleys of Shropshire. Henry married Kaye of Woodsome from who descend the

Langleys of Yorkshire. And Thomas de Langley the Lancastrian “Spin Doctor” who

we will hear more of in this history.

3. Richard, born about 1323.

It is the above

Richard de Longlegh or Longley from whom the Agecroft Hall Langleys

descend. He was originally intended for

the church, however a slight problem arose while at Oxford, the following

extract comes from records there.

Richard de Langeleghe from Lancashire

was found guilty of fatally stabbing another clerk in the neck with a bodkin at

Oxford on the evening of 16th March 1343.

Somehow he

managed to wriggle out of this, and was probably given the equivalent of a suit

case and a ticket to the colonies of the nineteenth century, which in those

days would have been a suit of armour a sword and a shield and sent off to

fight. This period contained many campaigns against the French, culminating in

the Battle of Crécy on August 26 1346 in which the English army defeated the

French.

Three years

after this, he was back in Lancashire, and married to Joan or Joanna de Tetlow

the 23-year-old eldest daughter of a neighbouring land owner, who was already,

or was shortly, courtesy of the Plague, to become an heiress.

For an overview

of the estates she was to inherit, and the resulting feuds, we must first take

a look at the Pendlebury and Prestwich families.

3. The Manor of Pendlebury[2].

Lies on the

west bank of the river Irwell, 4-5 miles north west of the centre of

Manchester.

In 1199 King

John confirmed a gift of “one carucate of land called Peneberi” to Ellis son of

Robert. The King had originally granted this land when he was Earl of Mortain

(1189-99) and confirmed the grant when he became King. The deed was signed by

the King at Le Mans in France and witnessed by Geoffrey, Archbishop of York,

the Bishops of Sarum and St. Andrews, the Earl of Leicester and the Archdeacon

of Wells as well as other gentry. Ellis is described elsewhere as Master

sergeant of Salford and a benefactor of Cockersand Abbey.

In 1212 the

Manors of Pendlebury and Shoresworth are given as being held by Ellis de

Pendlebury to the King in chief of[3] in

theynage[4] by

a rent of twelve shillings. Pendlebury was assessed as one ploughland and Shoresworth

as an oxgang.

Ellis died in

or about 1216 and his son Adam succeeded him. Little is known of Adam and his

son Roger the Clerk appears to have been in possession in 1246 and 1254.

The next

occupier was Ellis who came to a violent death in 1274 leaving a widow Amabel

and three daughters, Maud, Lettice and Beatrice.

In 1291,

William de Pendlebury, uncle to Ellis’s eldest daughter, Maud, claimed the

estate from her widower Adam de Pilkington who said he had the estate for life

because his wife, Maud, had borne him a daughter. The Jury who inquired found

that the daughter, Cecily, had lived for a short time and had been baptised.

However by 1297

the manor seems to have been in the hands of Adam de Prestwich, because in that

year he granted the manor to his son John. Then in 1300, Beatrice de

Pendlebury, Maud’s sister, released all her interest in the Manor of Pendlebury

to Adam de Prestwich.

So we come to

the Prestwich family.

4. The Manor of Prestwich[5]

Prestwich lies

on the east bank of the river Irwel to the north of the Manor of Tetlow which

was on the opposite bank of the Irwell to Pendlebury.

The first

recorded member of the family is Robert of Prestwich mentioned in a list of

adherents of Count John in his rebellion against his brother King Richard I. He

was fined 4 marks[6] to

regain possession of his inheritance which had been detained by the king as

security. Robert died before michaelmas 1206 and was succeeded by his son Adam

I who paid a further 5 marks to secure his father’s lands. In 1210 he held 10

bovates[7] in

Prestwich and Failsworth in Salfordshire in chief of the king in thenage. He

also held 4 bovates in Alkrington in the east of the parish of Prestwich under

Roger de Montbegon, Baron of Hornby.

The next

occupier was Thomas, but it is not certain how he was related to Adam I.

Thomas’s son

was Adam II who was married twice, his first wife’s name is not known but the

second is recorded as Agnes de Trafford. However it is not clear if this was

her father’s name or a territorial one. By Agnes he had a son Henry upon whom

he settled the manor of Wickleswick. William de Pendlebury in 1292 had given

this manor to Adam II, and in 1300 Beatrice de Pendlebury quit claimed her

rights in Pendlebury and Wickleswick to Adam II for £100. Wickleswick later passed

to the de Trafford family and is now known as Trafford Park.

In 1297 Adam II

granted his manors of Prestwich and Pendlebury to John his son and heir and

Emmota his wife and their heirs. Although these two produced two sons, the

property did not descend to them but to Adam II’s other son, Adam III. This may

have been caused by a family quarrel, which was patched up, and Adam III

reinstated.

Just how

Pendlebury passed to the Prestwich family is uncertain. There are a number of

theories:

1. Adam II’s mother was a Pendlebury.

2. Adam II’s first wife was a Pendlebury.

3. Adam II purchased Pendlebury.

4. The Prestwich and Pendlebury families

may have been one and the same; to wit there was a Robert de Pendlebury and

Robert de Prestwich at the same time, also the name Adam crops up frequently in

both families.

Adam III

married Alice c.1290 This Alice was known as Alice de Wolveley or de Wooley.

Her father was in fact Richard de Pontefact and the use by her and her son

Thomas, of the territorial name Wolveley caused much confusion among

genealogists until J.P.Eawaker calendared and transcribed the Agecroft Deeds in

about 1880.

Adam III and

Alice had two sons, Thomas and Robert, and three daughters, Alice, Joan and

Agnes. By the normal rules of inheritance, the oldest son, Thomas, would

inherit all the land (the entail) and the younger children would be provided

for out of any money or personal property left by their parents. However, it

seems that Adam and Alice wished to provide more fully for their younger son by

leaving him the Manor of Pendlebury. To do this, they entered into a collusive

deed to break the entail. In 1311 Alice and Adam both claimed that Alice

originally gave the property to Adam, even though both knew this was not true.

Adam then “gave” the manor of Pendlebury back to Alice for her life. The full

deed follows:

This is the

final agreement made in the Court of the Lord the King at Westminster in the

Octave of St. Martin (Nov. 18) 5 Edward II (1311). Before William de Bereford,

Lambert de Trikyngham, Henry de Stanton, John de Benstede, and Henry le Scrop,

Justices, and other faithful people of the lord the King then being present.

Between Alice daughter of Richard de Pontefract, plaintiff, and Adam de

Prestwych, deforciant. Of the Manor of Penilbury and of 40 acres of land, with

the appurtenances, in Prestwych. Whereupon a plea of covenant was summoned

between them in the same Court, that is to say, the said Alice acknowledged the

aforesaid tenement with the appurtenances to be the right of the said Adam, as

that which the same Adam had of the gift of the said Alice. And for this

acknowledgement, fine, and agreement, the said Adam grants to the said Alice

the aforesaid manor and 20 acres of land with the appurtenances of the said 40

acres of land, and the same surrendered to the said Alice in the same Court. To

have and to hold to the said Alice of the said Adam and his heirs during the

life of the said Alice Yielding therefore yearly one rose at the feast of the

Nativity of St. John the Baptist (June 24) for all services &c. to the said

Adam and his heirs belonging, and yielding to the chief Lords of the fee for

the said Adam and his heirs, all services which to that parcel of land belong.

And after the decease of the said Alice the aforesaid tenement shall remain to

Robert son of the said Alice and the heirs of his body, to hold of the said

Adam and his heirs by the service aforesaid, for ever. And if the said Robert

die without issue of his body, then the said tenement shall remain to Alice

sister of the said Robert, and the heirs of her body, to hold as aforesaid, for

ever. And if the said Alice sister of the said Robert shall died without issue,

then the said tenement shall remain to Agnes sister of the said Alice sister of

the said Robert, and the heirs of her body in manner aforesaid, for ever. With clause of warranty.

And if the said Agnes shall die without

issue, then the said tenement shall wholly remain to the said Adam and his

heirs, to hold of the chief lord of the fee by the service which to that tenement

belongs, for ever.

However, two

years later in 1313 there was a similar collusive deed, this time between Adam

and his eldest son, Thomas, who is described as Thomas de Wooley, in which all

three manors were again left to Alice, but on her death they would all go to

Thomas. This was not legal as far as Pendlebury was concerned, since that manor

already belonged to Alice, so Adam could not re-grant it, and is especially

curious since both deeds were “final agreements” decided in the King’s Court at

Westminster under the same four justices. This fine or deed was to be the

subject of dispute for the remainder of the century

In 1310 Adam

III was summoned to attend the King Edward II at London as a Knight. He died

about 1318 and certainly before 1321/22 when Alice, who now held all the

manors, petitioned the King for redress against the men of Cheshire who had

entered her land and taken goods worth £200.

In 1331, Alice

de Prestwich aka de Wooley died, and the trouble started.

It would appear

that after his mother’s death, Thomas hoped that the fine of 1311 in Robert’s

favour was lost, because he leased all three manors to Richard de Radcliffe to

use for his life for a fee of 100 marks of silver. “Let all present and future

know that I Thomas son of Adam de Prestwich and Alice de Wolueley have given

and granted to Richard son of William de Radcliffe, my manors of Prestwich,

Alcrinton and Pennebury with their appurtenances.”[8]

(Thomas had inherited the manor of Wooley from

his mother and was probably living there)

But Robert

produced his deed in the King’s Court at Westminster, and claimed his right to

Pendlebury. Thomas and de Radcliffe were called to answer the claim, but they

did not appear so Robert won his case and entered

Pendlebury.

Thomas retained Prestwich and Alkrington and re-confirmed the lease to

Radcliffe in 1333[9]. But it

was not until 1345 that Thomas relinquished all claims to Robert’s lands in

Salford[10]

About 1349,

Robert de Prestwich of Pendlebury died without issue, and so, according to the

1311 fine, Pendlebury passed via his deceased sister Alice who had married

Jordan, son of Adam de Tetlow of Broughton in 1325 to her eldest daughter,

Joanna de Langley (both her sons had died).

In about 1346,

Thomas de Prestwich (de Wooley), Adam and Alice’s eldest son died leaving two

daughters to co-inherit Prestwich. But

since both were underage they became wards of Henry, 4th Duke of

Lancaster, who, according to custom, appointed a guardian for them. This was

Richard de Radcliffe, who still occupied Prestwich.

In about 1350

the eldest daughter, Margaret, was placed in a Benedictine Convent at Seton in

Cumberland where she apparently took her vows on November 26, 1360. Radcliffe

then proceeded to marry the youngest daughter, Agnes, to his son John de

Radcliffe, thus neatly keeping a half share of Prestwich for the Radcliffes.

However there

was more to it than this, as a nun can not inherit or own any property, the

Radcliffes could now claim full title to the Manor after the death of Thomas’s

widow, Alice, which occurred in February 1356/7.

In this plan

however, they were thwarted, as Agnes died in 1362 without issue seized of the

whole of the manor, advowson etc. of Prestwich.

In accordance

with the remainder clause of the 1311 fine, the manor of Prestwich now passed

to the person next in line, namely her first cousin, Joanna de Langley.

But then Robert

de Holland turned up. First however we must return to the Langley family.

5. The Langley Family

5.1.

RICHARD

DE LANGLEGH – c.1325 to c. 1369.

When we left

the Langley family, Richard or Richard de Langlegh as the name was written, had

married Joan de Tetlow. Whether her future inheritance was already guessed at

is unknown. Probably it was clear that Joan’s Uncle Roger was approaching

middle age and childless. However it would appear that the plague of 1349,

which depleted the population by one third, speeded things up. When Roger de

Prestwich died, the Manor of Pendlebury passed to his sister Alice de Tetlow

who had died, as had her two sons, so this left Alice’s eldest daughter Joanna

de Langley as heiress to both the Manors of Pendlebury and Tetlow.

In February

1351/2 Richard de Langley and Joan were parties to a fine on the manor of

Pendlebury and of seven messages and 405 acres in Broughton[11],

Chetham, Crompton, Oldham and Wernyth by which these properties were settled on

Joan and her husband and the heirs of their bodies. In default the remainder to

William de Walden (Walton) and his wife Katherine who was Joan’s sister.

William de Langley, Rector of Middleton, acted as guarantor.

From a deed of

1369 it would appear that Richard and Joan lived at Tetlow. There is reference

to only one child being born to them; this was Roger the son and heir in 1360.

As this was ten years after their marriage, it must be assumed there were other

children. There may have been daughters or sons who died early, there was a

return of the plague in 1361 that might account for this, or it is possible

that Richard spent a lot of time fighting in France.

When Agnes de

Radcliffe, wife of John de Radcliffe, died in 1362. Her father in law, Richard

de Radcliffe, who had been granted Prestwich by Thomas de Prestwich (aka de

Wooley) acknowledged the right of Richard and Joan de Langley to the manor of

Prestwich and the advowson of the church. In return for this acknowledgement,

Richard and Joanna made an agreement in March 1366/7 to levy a fine on the

manor of Prestwich to the use of Richard de Radcliffe and his wife Isabella.

The Radcliffes agreed to support the Langleys interests against any external

interference (an allusion that will be shortly seen to Robert de Holland.)

Richard de Langley died shortly after this (before October 1369) when his son

and heir, Roger, was only 9 years old. The Babes in the Wood legend suggests

that he died fighting in France.

5.2.

ROGER DE LANGLEY – 1360 to 1393.

Roger was born

about 1360 (when his mother died in 1374 his age is given as 14). Either

shortly before or after his father’s death in about 1369, he was married at the

young age of 8 or 9 to Margaret or Marjorie, daughter of Sir Thomas Booth of

Barton. Marriages as young as this were common at the time for the purposes of

holding land and providing heirs. In 1369, his mother Joanna granted lands in

Tetlowe, Alkrington and Oldham to him and his wife.

Roger, as a

minor, now came under the guardianship of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster.

In 1371 Robert

de Holland appeared on the scene, claiming he was married to Margaret de

Prestwich (the nun) and so entitled to Prestwich and the Radcliffes quit claimed

the manor and advowson of Prestwich in favour of him and his “wife” Margaret de

Prestwich.

Shortly

afterwards, Isabella de Radcliffe now widowed, realised they had made a mistake

and entered into a bond with the young Roger de Langley for the payment of 100

marks. She agreed to compound this over the next seven years or remit entirely

if Roger could protect her from loss as a result of Prestwich being occupied by

Robert and Margaret de Holland or better still get Margaret canonically

recalled to her convent at Seton in Cumberland.

In 1374 Joan de Langley died, and John de Botiller,

Sheriff of Lancashire, took control of the estates on behalf of the Duke of

Lancaster on account of the minority of Roger. However, to quote the legend[12].

On the morning of the Feast of Ascension

in 1374, the villainous Robert de Holland "with many others assembled with

him, armed in breast plates and with swords, and bows and arrows, by force took

possession of the said lordship of the duke, in defiance of the Sheriff, and to

the contempt of the Lord Duke".

There are many

versions of the story handed down, that the young Roger and either his sister,

or his young bride were kidnapped by Holland and managed to escape, or that

they fled from Tetlow before Holland arrived heading westward towards the

Irwell river and Pendlebury beyond it.

Young

Langley and his sister escaped to the shelter of the forest which covered the

slopes of the Irwell valley, cared for by loyal retainers until Lancaster

rescued them.

In the modern

day pantomime “Babes in the Wood”, which folklorists believe is based on the

above event, the credit for their rescue is given to Robin Hood.

The “John of

Gaunt Window” in Agecroft Hall, which Roger later built, is said to have been

placed there as a tribute to Lancaster for his help.

In 1375/6

Robert and Margaret de Holland quit claimed on behalf of themselves and their

heirs to Roger de Longlegh and the heirs of his body all their rights and

claims in all those lands and tenements whereof Robert, son of Alice de Wooley,

was seized in the Vills of Pendlebury, Achecroft and Prestwich. This is the

first mention of Agecroft, but as a village not the family seat.

A week later on the 19 February, the Hollands

concluded the agreement with Roger confirming the quit claim of the previous

week, while Roger released to the Hollands all his claim in the lands belonging

to Thomas, son of Adam de Prestwich and the advowson and half of Alkrington.

Ownership of the other half was to be the subject of arbitration. However if the

Hollands were to die without heirs the lands were to follow the fine of 1313

and revert to Roger.

Things

quietened down a bit after this. Roger collected his bride, and it would appear

he was in the Dukes household, as their eldest son, Robert, was born at

Huntingdon on 6th June 1378 and was baptised at Eccles. Roger and Marjorie now settled back in

Lancashire and set about the building of Agecroft Hall where they were living

when a deed was signed in 1390.

In 1389 there

was an affray at Spotland near Rochdale between rival factions led by Robert de

Holland and William de Radcliffe. Robert and his friends and retainers ambushed

Radcliffe as he rode home from Rochdale. William escaped safely through the

shower of arrows and, reaching his manor, gathered together his sons, William

Richard and Robert, with Robert de Howarth and William Jenkinson, his friends

and a party of servants. They came upon the Holland faction with swords, bows

and other weapons “to the great fear of the whole parish there assembled”.

In the same

year – 1389 – Robert de Holland appeared before the justices of the County on

account of his involvement in a number of other affrays or trespass (some

involving some of the same people as that at Spotland). He admitted these and

was fined £10. Evidence was also given on his seizure of the manor of Prestwich

but this was not finally decided until 1394, although there is a suggestion

that the left Prestwich at this time.

Roger died on

26 October 1393 aged 33 leaving three sons that we know of: Robert his heir,

Henry a clerk who occurs in 1404 and Thurston, the first Langley Rector of

Prestwich. Roger’s inquisition gives him as holding the manor of Pendlebury as

one ploughland at the rent of sixteen shillings and a messuage called Agecroft

the family seat by a rent of six and eight pence.

The Escheator

of Lancashire at Prestwich assigned his widow dower in 1394[13]

She was to have a reasonable part of the manor of Prestwich together with the

hamlet of Alkrington among a long list of holdings including

the chapel at

Prestwich and a stable near hand. She was also assigned a third part of all

houses in Achecroft. This would seem to confirm that Prestwich and Pendlebury

were now firmly in the hands of the Langleys.

5.3.

ROBERT

DE LANGLEY – 1378 to 1447.

Robert was 15

when his father died; however he had already been married to Katherine, the

daughter of William de Atherton in 1391. The conditions of the marriage

agreement made between his father and William are complicated, but Robert and

Katherine were to have land in Pendlebury, Oldham and Crompton and property in

the vills of Broughton and Chetham “called Tetlawe”

The Prestwich

problem was finally wrapped up in 1394. In August of that year the trial before

the justices that had begun in the court of the Duchy 1389 (to determine the

dues from the manor of Prestwich) came to an end.

The Archbishop

of York who had been making enquiries on behalf of the King (Richard II) sent a

certificate dated 28 June 1394 to the king declaring that; “Margaret daughter of

Thomas, son of Alice de Wolveley was a nun and professed in the house of the

nuns of Seaton.” Robert de Holland denied at the trial that Margaret was a nun

professed, and Margaret herself appealed for dispensation on the grounds that.

“In her eighth year, or thereabouts, certain of her friends compelled her

against her will to enter the Priory of Nuns of Seton, Order of St. Augustine,

and to take on her the habit of a novice.

She had remained there as in a prison for several years, always

protesting that she never had made nor ever would willingly make any

profession. And seeing that profession must exclude her from her inheritance,

she feigned herself sick and took to her bed.

But this did not prevent her being carried to the church at the instance

of her rivals, and blessed by a monk in spite of her cries and protests that

she would not remain in that priory or in any other Order. On the first opportunity she went forth from

the priory, without leave and returned to the world, which in her heart she had

never left, and married Robert de Holand, publicly, after banns, and had

issue”.

However the

judgement went against them and Robert de Holland was ordered to pay to the

Duke the profits of the manor for the last five of the seven years 1374-1381

i.e. during Rogers’s minority.

We will

probably never know the true facts, but I suspect that Richard de Radcliffe, as

her guardian, had her placed there in order to obtain the entire estate for his

son who he had married to Agnes. Just why, as a result of this, she and de

Hollands children did not inherit Prestwich is a mystery.

In 1398 John of

Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster issued a writ freeing Robert de Langley from a rent

charge of 11 marks.[14]

The deed states that the Duke had previously granted to Robert, being under age

and in our wardship, the wardship of Prestwich and Alkrington “being in our own

hands because of his minority” for which he was required to pay the 11 marks

rent. The writ continues “And whereas we have retained the said Robert with us

for our service for the term of his life and for the good and agreeable service

which he has to us done and will do. We have pardoned and released to him the

rent for the previous year and until he come of age in 1399.

It was

customary at that time for sons to be sent to live in the households of the

local Lords – a bit like being sent to boarding school – and from the above it

would appear that Robert may very easily have spent his youth in Gaunt’s

household. He would however have had at least one relation there, this was his

second cousin, Thomas de Langley, who was Gaunt’s clerk and chief advisor.

In 1400 Robert

started handling his own affairs, and presented Geoffrey de Frere as Rector of

Prestwich. However the king disallowed this, probably because Robert had failed

to make proof of age until 1402 and the king appointed Nicholas Tyldesley

instead.

It would appear

that a certain John Pilkington occupied the Manor of Prestwich at about this

time, possibly as local guardian for Robert

In December

1401 Robert de Holland surrendered to Robert all claims on the manors of

Prestwich, Alkrington and Pendlebury. He also agreed to hand over the deeds in

exchange for 5 marks a year for life this would continue for the lives of his

four sons if they did the same.

In 1402, Robert

de Holland pushed matters too far. He was described as a noted swashbuckler,

and had been outlawed for treason. Having burnt a house, and on two occasions

driven cattle away from Prestwich; Robert de Langley went after him and

captured him at Glossop. But as would happen today happened then, and Robert de

Langley was accused of a breach of the peace. However with his connections at

Court, Robert was pardoned by the king who described him as having been in the

King’s service “after our coming to England”.

In 1417, Robert

presented his brother Thurston, as Rector of Prestwich upon the death of

Nicholas de Tyldesley and after his death in 1436 he presented his son Peter.

Robert died

aged 68 in 1446, his mother Margaret was still alive and living at Tetlow which

appears to have been the family dower house as his widow Katherine now retired

there.

Robert and

Katherine left the following children.

1. Thomas, the heir.

2. Piers, mentioned in a marriage settlement of

1412[15]

3. Peter, Rector of Prestwich 1436 to 1445

4. John, mentioned as defendant in an Alkrington

case in 1470.

5. Ralph, succeeded his brother Peter as Rector

of Prestwich. In 1465 he became Warden of Manchester Collegiate Church. He died

in 1493 and was buried in the Rector’s chapel in Prestwich. I have a note to

say that he was knighted and his coat of arms is given as Argent, a cockatrice

sable beaked and wattled gules; this is the earliest reference I have to the

Langley arms.

Although to date, this history has concentrated on facts gleaned from

deeds and fines. It was at

this stage of the family history that I started to look at the historical

background of the times, and wonder what part the family might have played in

them and what social gatherings might have taken place.

In 1398 things

started to go wrong for the Lancastrian family. King Richard II exiled Henry

Bolingbroke, (Gaunt’s eldest son) for ten years. Then on February 3rd

1399 Gaunt died at Leicester. We can only imagine that Robert de Langley was in

the Duke’s household at the time, and accompanied the Dukes body on the trip to

London where he was buried in St. Paul’s on 16th March.

Shortly after

this King Richard II extended Bolingbroke’s exile to life and confiscated his

estates dividing them amongst his cronies.

On June 6th 1399, Robert reached his maturity. Was this

celebrated at Agecroft? And did it help change the course of English history?

Present would have been representatives of all the great Lancastrian families:

Ashetons, Atthertons, Bartons, Booths, Chethams, Radcliffes, Traffords, William

de Langley of Middleton, with his brother Thomas,

Thomas, now the executor of Gaunt’s will and consequently responsible for

the Lancastrian estates, was ostensibly there for the celebrations, but had he

other reasons?

We can well imagine the topics of conversation. The worsening political

climate. The continued megalomania of Richard II who was currently on campaign

in Ireland; the exiling for life of Gaunt’s son Bolingbroke now Duke of

Lancaster; the confiscation of Bolingbroke’s inheritance which had been divided

amongst the king’s cronies, one of whom would shortly become their over lord.

Wandering amongst the gathering, having a word here, another word there,

reminder of a debt owed, a favour recalled. Stirring up worries, subtly

offering solutions and sowing the seeds of revolt, was Thomas de Langley, who,

in his biography, Ian C. Sharman describes in today’s language as a spin-doctor

and fixer, a practitioner of the devious arts so well described 150 years after

his death by Machieveli.

Are the above celebrations and events all in my mind?

We know that Robert was 21 on 6th June 1399.

Historical documents record that Thomas de Langley was in Lancashire at

the end of May early June of that year. (If he were, surely he would have

attended his cousin’s celebrations?)

More historical data shows that Thomas de Langley arrived with about 300

knights at Pontifact towards the end of June to meet up with Bolingbroke, who

had returned from France, with fifteen supporters.

The wording of deeds would indicate that Robert was with him.

Upon meeting up

at Pontifact, Bolingbroke made Thomas his secretary and presented him with the

ducal signet, effectively giving him the control of all his affairs, and

consequently making him one of his closest advisors[16].

During the

summer they travelled through the country picking up more supporters until at

Chester they came upon King Richard II who had hastily returned from Ireland.

Richard was persuaded to abdicate and Bolingbroke was crowned Henry IV on 13

October, and so the House of Lancaster was formed.

It would be

nice to think that the basis for these events was formulated in the great hall

at Agecroft.

5.4.

SIR

THOMAS of Agecroft 1407-1472

Sir Thomas

succeeded his father at Agecroft in 1446. In a Kings Licence dated at Scroby on

6 May 1460 and granted to Archbishop William Boothe and others. Thomas and his

father, Robert, were mentioned by name to be specially prayed for in the

chantry of St Katherine in Eccles Church. He married Margaret, dau. of Sir John

de Asheton, and died in 1472 leaving two sons that I know of.

Rev Ralph, Rector of Prestwich, he was

a BD and was instituted 1st May 1493 he resigned 4th

September 1498.

John,

of Agecroft. His heir.

5.5.

JOHN

of Agecroft died 1496

He married 1st

the widow of Osbaldstone, and they had two children:

(ii)

Nicholas.

(ii)

Katherine.

John

married 2nd Maud, dau. of James Radcliffe and by her had 8 children.

(ii) Rev. Thomas, his brother Robert, presented him as Rector of

Prestwich in 1498, and he is described as the friend of Hugh Oldham Bishop of

Exeter. He was executor of the will of Isabel, widow of Robert Chetham. In 1523

he is described as Sir Thomas Langley late Parson of Prestwich and occurs along

with Sir William Langley now Parson of the same.

(ii)

Robert born 1462, his heir.

(ii) Ralph,

(ii) Margaret, married

Godfrey Shakerley, son of Peter Shakerley of Shakerley.

(ii)

Agnes,

(ii) James,

(ii) William,

(ii) Richard,

5.6.

ROBERT

of Agecroft, 1462 to 1528

Born 1462 and died in 1528, (Burkes is

incorrect in giving is death as 1512) having married Eleanor, dau. of William

Radcliffe of Ordsal.

His will is as follows:

In dei noie

amen Anno dui Memo Dmo XXIIIj mo die mensis februarij vicesion secudo (1524-5)Ego Robert Langley armig copos ment

et Sane Memorie (videns mudu hui fore Caducu ejsg times fragilitatem et ne

subito me mors occupet) Condo meu testametu siue meam ultiam Volutatem in hoc

modu. In Pinis lego aia mea deo oipotenti the marie iobsq sus et Corpus quoq

meu sepeliend in nua capella ex pte australi pochialis ecclie bte Marie de

Pstwyche. It lego meu au iu noie

mortuarij mei. It when my funale expenss

and my detts ben payed I will the residue of my goods by my executors be devided

into iij pats. On pte therof to the

performance of this my will as here after dothe ensue. It the secude pte therof

to Aelenore my wiff. It the thride pte therof unto my ij sons Edmund Longley

and Lawrens Langley equaly by my executors to be devyded to theym.

It I will my executors shall take of my said

thryde pte to ye flagging of ye flore of ye said new chapell.

It I beqwith to ye building of ye poche churche

of owre lady of eccles vj Li. Xiij s. iiij d. to be payed and delyvered to ye

said werke by executors as the werke gothe furthe.

It I will that if any goods of my said pte

doythe remayne my executors shall dispose it as they shall think most

convenient.

It I beqweth to my Cosyn Robert Langley heire

apparent unto me. The said Robert a sylu pese wt a Cou to ye same. My best

fether-bedde ij couletts ij blankets a payre of schets, a bolstar and ij peloys

my best hangying of ye chamber wt ye best couying belongying to ye same bedde.

Also all thyges appartenying unto ye chapell that is to wit A chales, a masse

boke, al vestiments for a pst to say masse wt and altare portatile wt oye

cloths belongyng to ye awt. Also I

beqweth to the said Rovert on wayne a plygh wit ij yoke oxen my gratts potte

sylu spones and a dosen of brode pewt dyschys a dosen of narrow pewt dyschus.

Also all things applenying unto ye hall as qwecionse wt ye hengyng of ye hall.

Itm I beqweth unto my dought Anne grenehalgh ij

kew wt ij calves.

Itm I will yt Elenore Longley and Johanee

Longley doghters of my son Thomas Longley if they will be rulet and conselde by

theyre broy Robert Longley and by my executors and also upon condicion yt

Cicile my doght in lowe late wife to my foresaid son Thomas Langley will be gud

and kinde unto Thomas Schols his wiff

and chulderyn and unto all oy of hyr tenants either of them v marks toworde

theyre mariages.

Item I will on trentall of masses be songyn for

me as Pstwych ye daye of my buriall if so many psts can yed that daye to saye

masse.

Itm I will an oy trentall of masses shall be

sayed for my sawle at Machest as hasterly as can be aftre my decesse all opon

an oy daye.

Itm

I will the said John Mosse shall do and saye sui at Pstwyche for on yere for my

sawle and all Chystyn sawls and shall hafe for his stipende vj markes wech vj

marks my executors shall take v of my pte of goods.

Itm. I order my executors my bro Thomas Langley late pson

of Pstwyche, my son William Langley pson of Pstwyche and Aelenowre my wiff. To

execute pforme and fulfill this my testament and last will accordyng to ye

pmiss. In witnesse wher of I the said

Robert Langley hafe set my seal and sigmanwell yeven the daye and ye aforesaid. Proved

at Chester 1 April 1528.

His widow,

Eleanor, also left a will, the following is an extract.

To

my cose Robert Langley Esq XXs It to my

cose Cecile his wyff vjs viiijd.

To

my doght Anne Grenehalgh iij Li a shodying bedde wt ye hengynge of ye said

bedde and an matares. Also to my son Edmund iij Li. To my son Laurans iij

Li. To my sister Clemens Chetham vjs

viijd. To Elenore Pstwych (Granddaughter) xxs. To ye doghts of my son Thomas

Langley, Elenore and Jone eyther of them xLs.

Also

I will that my son pson shall have my feather bedde.

To

ye wyff of Thomas Holland a pan. To Elenore Pstwych and Anne her sister a

coper. To Alys Rydych a materes and iijs iiijd. To the daughters of John

Grenehalgh, Elizabeth and Anne. Also my son Wyllm Langley Pson of Prestwich.

Robert and

Eleanor left the following children:

(i)

Anne, married John Greenhaugh.

(i)

Agnes, married Ralph Prestwich.

(i) Rev.

William, Rector of Prestwich, he was instituted in 1523. In October 1559 he

failed to attend a meeting of the Elizabethan Church, but later subscribed. In

1568 he was deprived of the living because his conscience would no longer allow

him to minister.

(i) Thomas,

married in 1518 to Cecile, dau. of William Davenport of Bromhall. Thomas

died in 1527, predeceasing his father and leaving the following children:

(ii)

Elenore, married Thomas Holland.

(ii)

Johane, married Robert Holt.

(ii) Sir Robert, succeeded his grandfather at Agecroft. He married

Cecile, dau of Sir Edmond de Trafford, and died 1561 leaving 4 daughters.

(iii)

Margaret, married 1st R

Holland, and 2nd John Reddish.

(iii)

Anne, of Agecroft, married William

Dauntsey.

(iii)

Dorothy, married James Assheton.

(iii)

Katherine, married Thomas Leigh.

(ii)

Ralph,

(ii) Rev. Thomas Graduated from Jesus College Cambridge with his BA in

1537. The following year he became secretary to Archbishop Cranmer of

Canterbury. Thomas Cranmer had been born in Nottingham and attached himself to

the Boleyn family who were prominent at court during the sixteenth century. He

supported Henry VIII in 1533 in his break with Rome so that he could marry Ann

Boleyn. Henry’s view that England should remain Roman Catholic but with himself

as head of the church rather than the Pope was supported by Cranmer, who was an

idealist rather than a leader, and resulted in his translation to Archbishop of

Canterbury. When Thomas Langley became his secretary Anne Boleyn and been

beheaded and Jane Seymour had just died giving birth to Edward. It was during

the remaining nine years of Henry’s reign that Cranmer, presumably with the

help of Thomas, compiled the new English prayer book, which was published in

1548 when Edward with his Protestant advisors had been on the throne for a

year. With this work completed, Thomas became Rector of Boughton Malherbe in

Kent. The death of Edward in 1553 saw the end of Protestantism with the reign

of Mary who brought England back to the pope. Cranmer was first of all

imprisoned in the Tower, and then because he would not recant, he was burnt at

the stake in Oxford. Thomas and other Protestants, fearing the same fate, fled

the country and he was admitted to the English Church and Congregation at

Geneva in 1556.

With

the reign of Elizabeth, Thomas returned to England and was presented by the

Queen to the Rectory of Welford in Berkshire on 7th December 1559

having already been given a Canoncy at Winchester by the Crown on 6th

October.

After 12 years of study he was admitted

BD at Oxford on 15th july 1560.In 1563 he was presented to the Vicarage

of Warbourough Wiltshire. He wrote many religious books and thesis during his

lifetime. His will was dated 22nd December 1581 and he died before

the end of the year.

(i)

Edmund,

(i) Laurence, our ancestor.

5.7.

LAURENCE

LANGLEY

Laurence married Katherine and left 3 children.

(i) Robert, married Mabel, dau of Thomas

Tiddersley of Wardley and had issue

(ii) Thomas, of Brasenose Coll Oxford 1579, married and had a son, William, Rector of Cheadle Staffs, he

married Katherine Assheton, Chadderton.

The following

is an extract from an essay found amongst the Assheton papers at Chadderton,

although the dates do not seem to fit, I believe it to have been written by

Thomas, William’s father.

“I was borne at Prestwiche

anno christi 1596. My father M. Langley beign at that time curet to his cosen

who was ye parson there. I was brought up there in my youth, and went to ye

Gramar Schole at Manchester where I received good instruction in gramar

learninge before I was enterd at

Bragennose Colledge Oxon. My father being wrought upon by Mr William Langley

and M Asheton of Chadderton to send me there. I was from my youth given to

industry and was seasoned well with pure religion and letters so that after I

commenced Master of Arts I was chosen to read the humanity lecture.

When

I was a child I did as the apostle says children doe, I was tempted with luste

and after was frequently troubled with fits of incontinence many times.

Nor

did I ever before I went to Oxon drink a helath, but at Oxford I quickly began

to drink healths with so doing I was twice extremely sick upon my first wakeing

fynding my stomak sore opprest I did arise about three of clock and went into

the fellows gardinge for it was somer, when I sat down was so vehemently

opprest with payne that I thought I should have dyed instantly. Whereupon I

vehemently lift up my heart to God that he would pardon me and preserve me at t

his time and I would never do so agayn. Whereupon I instantly vomited apples

which I had eaten, which had been so parched and dryed in ye stomak that there

was no ioyce of moysture remayning in them. And presently after I was rid of

payn and felt very well again.”

I

believe the following people also fit in as children of the above Robert,

although their mother’s name is given as Isabel.

(ii)

Lawrence, born 1570, entered

Brasenose College, Oxford 1588.

(ii)

Edward, christened in Manchester

Cathedral 1 Dec. 1573.

(ii) William, christened in Manchester Cathedral 16 Jan, 1575.

(ii) Alice, christened in Manchester Cathedral 24 July 1577.

(ii) Margaret, christened in Manchester Cathedral 8 July 1580.

(ii) John, christened in Manchester Cathedral 12 Dec. 1581.

(i) Isabel,

(i) Rev.

William MA. the eldest son, Rector of Prestwich 1568 – 1611 and died at

Prestwich 14 Oct. 1613. He married Anne who died 1627, they left 7 children.

(ii)

Deodatus, married 9 Nov. 1612, Maria

Edge of Prestwich and died 1623 leaving 5 children.

(iii) Thomas, christened at Prestwich 24 Oct 1613.

(iii) William, christened at Prestwich 18 Oct 1615.

(iii) Henry, christened at Prestwich 23 Aug 1618. See

Langleys of Ireland.

(iii) Dorothea, christened at Prestwich 6 Jan 1620. Living at Bury in

1666.

(iii) Edmond, christened at Prestwich 5 May 1622

(ii) John, Rector of Prestwich 1611-1632 Educated at Cambridge, married

Alicia, (she d. May 1629 and was buried in Prestwich 11 May) John d. Aug. 1632

and was buried at Prestwich 16 Aug).

(iii) William, born 1611.

(iii) Anna, christened at Prestwich 4 Oct 1612, married 14 Aug 1634 to

Edmond Tetlow.

(ii)

Mathias, married Mary Moore. Registered his arms as the Mermaid and

Cockatrice quartered.

(iii) William married Jane Broom.

(iv) William. Rector of Lichfield

(iv)

Mathias.

(iv) Ralfe.

(iv)

Joy.

(iv)

Jane.

(iii) John.

(iii) Joan.

(iii) Ellen.

(iii) Anne.

(ii) William.

(ii) James.

(ii) Elizabeth, married 1604 John Glover.

(ii) Elinor, married 1606 William Edge.